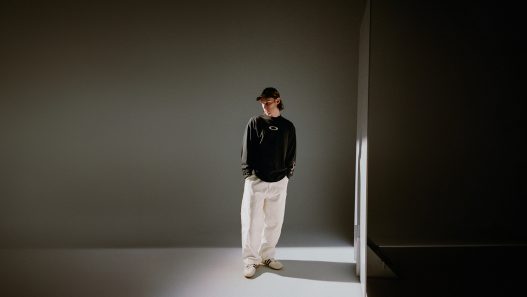

In the hazy, humming underbelly of Brooklyn‘s experimental scene, World’s Museum—the alias of Will Burghard, a multi-instrumentalist who’s been chasing sonic ghosts since he first tinkered with keys at age five—crafts worlds that blur the line between the organic pulse of nature and the glitchy hum of our wired existence, weaving classical roots with vintage synths, toy circuits, and field recordings into a genre-defying brew of ambient electronica that’s as intimate as it is expansive. With two self-released EPs and a full-length already under his belt, Burghard just dropped his most assured statement yet, the Bizenteo album on Shimmering Moods Records last month, a collection of tone poems born from years of scavenging sounds that linger like echoes in empty rooms, complete with the spectral single ‘Death on the Pub Crawl’ that feels like a midnight confession set to flickering neon.

Now, as the dust settles on Bizenteo‘s release, he pulls back the curtain in this interview on the inspirations and back story.

You’ve been making music since you were a kid tinkering with keys at five—what’s one childhood memory that still sneaks into your compositions today?

I remember when I was a kid, I got very ill with a fever and was in bed for a few days, and my mom would put on these CD’s of Satie on this little boombox we had while I drifted in and out of sleep. It was really perfect music for being in that fever-dream like state, and it influenced my predilection towards music that can sort of float in your subconscious.

Growing up with a classical background in New York, how did that foundation collide with your love for synths and electronic sounds to shape the way you approach songwriting?

I think synths and electronic sounds are kind of a natural progression of the sounds that classical composers began experimenting with in the early 20th century. I grew up playing piano and naturally an interest in synthesizers grew from that. I started listening to electronic music at the same time that I was exploring romantic and modernist composers. It’s all just experimenting with tones and colors. I think I definitely approach songwriting more like classical composers than like rock or pop songwriters, but that also fluctuates.

With Bizenteo fresh out on Shimmering Moods Records, what was the spark that turned those self-released EPs into this fuller, more structured album?

Every release I put out sort of represents a pocket of time when I was fixated on a certain set of ideas or sounds. A lot of the self-released material I put out was stuff I wrote a long time ago as a teenager, but this is all very new material. I guess I felt inspired to spend a little bit more time fleshing this one out musically and conceptually because it was newer material and it just felt worth it. I usually gather similar sounding tracks as I’m writing them and a vague concept emerges from that, not the other way around.

You mention drawing from Erik Satie and Brian Eno’s “furniture music” idea—how did you weave that subtlety into tracks that feel like classical pieces rather than drifting drones?

I think Satie and to some degree Eno represent a camp of ambient music that is more rooted in melodic and harmonic phrasing, the other camp being the drone artists who focus on expansive explorations of tone and texture. My songwriting is more rooted in the former, especially on this record. There’s certainly drone elements on the record, but with most of it I was really exploring melody and harmony, seeing if I could write really coherent musical phrases. It’s an interesting challenge to write melodic music that can just sink into the background.

On ‘Death on the Pub Crawl’, there’s this eerie pub-haze vibe—walk us through the field recordings or moments that birthed that track’s ghostly heartbeat?

I mostly wrote that track on an old Yamaha DX7 that was handed down from a family member. I recorded myself smashing beer bottles into a bowl to accentuate the phrasing of the chords, and also because I felt antsy writing electronic music on a computer and wanted to make some kind of physical sound. I guess that’s where the name came from, I’m not really sure.

Your work explores those human imprints in physical spaces, like echoes in empty rooms—what’s a real-life spot in New York that left the strongest mark on Bizenteo?

It’s hard to think of a single spot because the entire city of New York is covered in the residual presences of humans. You basically can’t go anywhere in the five boroughs without seeing signs of people. I suppose living among that and recording music in it is what influenced the album as a whole; the fact that the presence of humans is practically inescapable.

Bringing your ambient sets to intimate spots like The Secret Pour and Pete’s Candy Store must feel electric—how does playing live shift the way listeners inhabit your subtle sound worlds?

The challenge in playing ambient music live is in turning music that is supposed to be able to fade into the background into an interesting and engaging performance where the focus is entirely on the music and the performer. So far my answer to that has been to actually perform as much of the music as I can, as opposed to standing behind a laptop the whole time. Going forward I really want to incorporate a more elaborate visual aspect as well. The last time I performed a bunch of people drew pictures while I played which I really loved and I think it matched the vibe of the performance.

As someone who’s blended nature’s whispers with media’s glitches, what’s the most unexpected “residual presence” you’ve captured that totally upended a track’s direction?

The track “Human Places” is actually just a demo recording that I made of a melody that I liked. I always record bits that I like on my phone when I’m noodling around so that I don’t forget them. Usually I re-record them for the finished track, but on that recording, I happened to capture some children playing outside my apartment window, and I thought it fit particularly well with the melody, so I decided to just use the demo recording as it was.

Diving into those themes of ghosts in media and spaces, has chasing these human footprints ever forced you to confront something uncomfortably personal in your own life?

I don’t think the act of writing this music in particular did, but releasing it definitely did. I made a bigger deal of this release than my previous ones (label, publicity, press etc) so I had to confront the trepidation I have about putting my music out there in front of people. It feels like I’ve spoiled a part of the music by putting it out there in a way, like I’m exposing a part of myself that is better kept secret. I think that’s just part of being an artist, but I have to get used to it.

If you could snag one wild field recording from anywhere right now to remix into your next project, what’s the spot and why would it make for killer “furniture music”?

As a matter of fact, my next project already features a plethora of field recordings. There are some seriously amazing bird and frog sounds coming out of Central and South America. They are the definition of furniture music because you can tune them out or tune into them and they are still interesting. Someday I’d like to capture a Montezuma Oropendola on recording. They have this call that sounds like a laser beam charging up and going off.

Stream Bizenteo:

Follow World’s Museum:

Spotify – Facebook – Instagram – Linktree